Want some career advice? Make sure that your name becomes synonymous with a key area of the company. It’s unlikely that they will fire John-the-IT-guy. You’ve reached your goal, if your colleagues and boss can’t imagine how the IT infrastructure of the company could ever function without you. At this point, it doesn’t matter if you’re lazy or screw up regularly. The association John<->IT becomes so ingrained in everyone’s head that whenever there’s a serious problem, you can easily convince your colleagues that it’s not your fault. You just didn’t have the resources you needed. Or a third party screwed up. In fact, serious problems are good for you. Every time there is a crisis, you can demand more money.

This may seem pretty obvious. What is less obvious to most people is exactly this trick is used by all kinds of institutions. The “company” in that case is society.

The military has managed to become synonymous with national security, churches with religion, universities with research, the police and prisons with security, and schools with education.

Most people can’t imagine a functioning society without these institutions. This is completely analogous to how in the example above, people can’t imagine a company without John-the-IT-guy.

And even if any of these institutions screw up badly or produce unsatisfactory results, their existence is never questioned. Instead, they are rewarded with more money – just as John-the-IT-guy. For example:

- Too many national security threats -> more money for the military.

- Too much crime -> more money for the police.

- Too little exciting research results -> more money for universities.

- Too many badly educated people -> more money for schools.

Ivan Illich calls this process escalation or social addiction and it can be characterized by the “tendency to prescribe increased treatment if smaller quantities have not yielded the desired results”.

If you don’t think too hard about it, this seems reasonable. In particular, you might want to argue that if John screws up, he certainly will be replaced by a more competent person. Of course! Let’s say that Bob replaces John. Bob-the-IT-guy might be a bit more competent or slightly less competent than John. But what really matters is that the company will always have IT problems and an IT guy. As long as the company remains trapped in the paradigm that it needs an IT guy, all improvements will be marginal at best. No IT-guy will be so stupid to improve the IT infrastructure in such a way that he becomes dispensable.

Applied to institutions, this observation is known as the Shirky principle, after Clay Shirky, who observed that “institutions will try to preserve the problem to which they are the solution.”

For example, for the military it was certainly true that “the higher the body count of dead Vietnamese, the more enemies the United States acquires around the world” and this, in turn, requires an even larger military. Similarly, “jail increases both the quality and the quantity of criminals, that, in fact, it often creates them out of mere nonconformists”. And “mental hospitals, nursing homes, and orphan asylums provide their clients with the destructive self-image of the psychotic, the overaged, or the waif, and provide a rationale for the existence of entire professions”.

With the Shirky principle in mind, it becomes obvious that “better” institutions never can bring satisfying solutions. Instead, we have to drop the paradigm that the institutions are synonymous with certain aspects of society. Once we do that, a world of possibilities opens up. If we move beyond the framework of institutions, there is a real chance at significant progress compared to the incremental progress that is possible in the institutional framework.

This is one of the key arguments Ivan Illich lays out in his book Deschooling Society. Interestingly, he completely overlooks the role of the state which, in some sense, is the meta institution that enables most other institutions. This logical gap was filled only three years after the publication of Deschooling Society by Murray Rothbard in his book The Anatomy of the State. Both books are similar in spirit, driven by indefinite optimism, which isn’t too surprising given that they were written shortly after the first moon landing. The main difference is that Rothbard declares “the state is the devil”, whereas Illich declares “schools are the devil”.

Illich passionately claims “deschooling is, therefore, at the root of any movement for human liberation.” and “School is the advertising agency which makes you believe that you need the society as it is.”

I think the case for these claims is much weaker and they’re less interesting than the general claim that the institutional framework is problematic. Nevertheless, it’s fortunate that Illich decides to focus on one key institution. Putting the magnifying glass on one of the institutions allows us to grasp the larger patterns and to think about concrete alternatives. And schools are a great choice because the existence of educational problems is something that everyone can agree on.

So in the following, I won’t treat Illich’s book as a pamphlet that declares “schools are the devil”. Instead, I’ll treat it as a case study for the general problems of institutions, and for how a society without institutions might function.

The trouble with schools

Before we can discuss how well schools fulfill their educational goals, we have to clarify what we’re talking about. The three most commonly proposed educational goals are:

- Homogenization.

- Intellectual Cultivation (Plato).

- Realization of Potential (Rousseau).

Typically, people who learn towards different dimensions, argue for different kinds of schools. Schools try to find compromises and thus inevitably fail to meet any of the goals. Even though Illich is an outspoken Level 2 thinker since he dismisses homogenization and intellectual cultivation completely, he correctly points out that new schools inspired by Rousseau’s vision will not bring significant improvements.

Before we can discuss how well schools fulfill their educational goals, we have to clarify what we’re talking about. The three most commonly proposed educational goals are:

One of the strongest arguments against schooling he discusses is discrimination. Currently, it’s completely normal to discriminate in hiring based on previous attendance at some curriculum. This, obviously, favors children with richer parents and also otherwise makes little sense. School years can often be translated as an “enforced stay in the company of teachers” and rarely says anything about how much someone understands.

Illich calls for dramatic measures: “To detach competence from curriculum, inquiries into a man’s learning history must be made taboo, like inquiries into his political affiliation, church attendance, lineage, sex habits, or racial background. Laws forbidding discrimination on the basis of prior schooling must be enacted. Laws, of course, cannot stop prejudice against the unschooled – nor are they meant to force anyone to intermarry with an autodidact but they can discourage unjustified discrimination.”

It’s hardly a controversial claim anymore that modern schools are mostly about signalling. (This issue is discussed more extensively in the book The Elephant in the Brain by Kevin Simler and Robin Hanson.) However, by invoking the word “discrimination” Illich manages to amplify the message.

Certification is not only problematic because it leads to discrimination but also because of the well-known cobra effect. One intention behind certification is certainly to motivate students to learn subjects more deeply. In reality, however, it’s completely normal that students are actively discouraged from doing the kind of curiosity driven deep dives into a subject that leads to truly deep understanding because it would affect their grades negatively.

An important related aspect is that certificates also plays an important role on the teacher side. There are lots of people who would love to share what they know with others. But in the current system, they’re effectively locked out from participating. Illich concludes: “Certification constitutes a form of market manipulation and is plausible only to a schooled mind.”

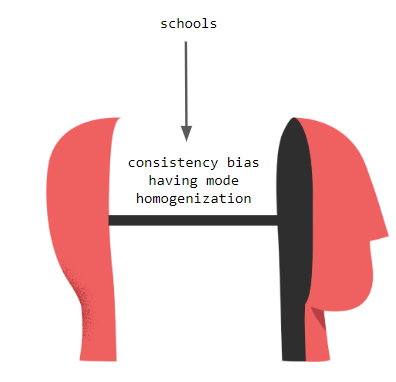

The observation that schools produce “schooled minds” is a further key argument. On the one hand, there is what Illich calls a “hidden curriculum” which aims to fulfill the homogenization goal mentioned above. Students learn not just about the history of Greece but also to follow orders and to work in silence on obviously nonsensical projects. (A great book dedicated to this issue is Disciplined Minds by Jeff Schmidt.)

On the other hand, the longer people attend school the more likely it is that they will defend the school system. It’s really hard to admit to yourself that you’ve wasted years of your life. The more comfortable option is to defend the current system to justify your decisions in the past. This is the well-known consistency bias. Since most people invest years of their lives into the school system, there is arguably no other area of life that is so heavily dominated by it.

A third problematic aspect of schools for the minds of students is that they corrupt their attitude towards learning and learning objects. The focus in school is primarily on achieving, having and consuming and rarely on growing and developing. To use the terminology introduced by Eric Fromm, while educational needs are clearly being needs, schools forces students into a having mode and addressing being needs from a having mode inevitably leads to unsatisfactory results. In schools, students are taught to use books, teachers, and their peers to their advantage in order to have better grades. In contrast, the being mode is characterized by a symbiotic relationship of mutual transformation.

Now, of course, it’s always easy to criticize without proposing an alternative. Luckily, Illich doesn’t fall into this trap. He proposes a concrete alternative which, even 50 years later, makes a lot of sense.

How can education work without schools?

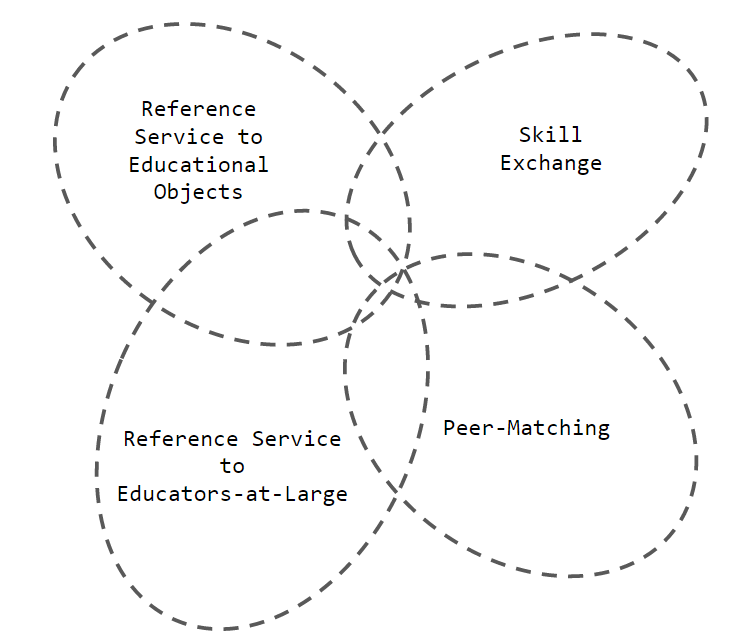

The alternative Ivan Illich proposes, which he calls “learning web” or “learning network” or “educational web”, has four key components:

- “Reference Services to Educational Objects – which facilitate access to things or processes used for formal learning. Some of these things can be reserved for this purpose, stored in libraries, rental agencies, laboratories, and showrooms like museums and theaters; others can be in daily use in factories, airports, or on farms, but made available to students as apprentices or on off hours.”

- “Skill Exchanges – which permit persons to list their skills, the conditions under which they are willing to serve as models for others who want to learn these skills, and the addresses at which they can be reached.”

- “Peer-Matching – a communications network which permits persons to describe the learning activity in which they wish to engage, in the hope of finding a partner for the inquiry.”

- “Reference Services to Educators-at-Large – who can be listed in a directory giving the addresses and self-descriptions of professionals, paraprofessionals, and freelancers, along with conditions of access to their services. Such educators, as we will see, could be chosen by polling or consulting their former clients.”

Thanks to the internet, access to learning objects has already become much easier and there are all kinds of skill exchanges like Codementor and italki. But what about the remaining two puzzle pieces?

To some extent, peer-matching is happening on social platforms like Twitter. But many people don’t have a large enough following on these platforms to find peers or are too introverted to reach out. A dedicated platform would be amazing and I’m not sure why it currently doesn’t exist.

Illich has a concrete vision for how it might function: “The operation of a peer-matching network would be simple. The user would identify himself by name and address and describe the activity for which he sought a peer. A computer would send him back the names and addresses of all those who had inserted the same description. […] People using the system would become known only to their potential peers. […] A complement to the computer could be a network of bulletin boards and classified newspaper ads, listing the activities for which the computer could not produce a match. No names would have to be given. Interested readers would then introduce their names into the system.”

Moreover, he emphasizes that the matchmaking should be based on common interest in a book, article, film or recording. Less specific matchmaking based on an idea, a topic, or issue are necessarily teacher-centered and hence less suitable for a peer-to-peer framework. “Theme-matching is by definition teacher-centered: it requires an authoritarian presence to define for the participants the starting point for their discussion.”

This matches my experience. I organized different “theme-matched” learning groups in the past, and they only worked well if there is someone more experienced who guides the group.

Another important observation by him is that whoever operates the learning web, should do their best to stay out of people’s way. “Today’s educational administrators are concerned with controlling teachers and students to the satisfaction of others-trustees, legislatures, and corporate executives. Network builders and administrators would have to demonstrate genius at keeping themselves, and others, out of people’s way, at facilitating encounters among students, skill models, educational leaders, and educational objects. Many persons now attracted to teaching are profoundly authoritarian and would not be able to assume this task: building educational exchanges would mean making it easy for people – especially the young – to pursue goals which might contradict the ideals of the traffic manager who makes the pursuit possible.”

The final puzzle piece, “Reference Services to Educators-at-Large”, currently doesn’t exist either although it’s arguably, the most important part. Most learning journeys will fail unless there is proper guidance, encouragement and support. These are things that teachers, at least in theory, provide in the current system. Unfortunately, most teachers are far too busy with other tasks to fulfill this role properly. By unbundling this piece of the educational puzzle, teachers who are passionate about guidance, encouragement and support could dedicate all their energy in that direction.

The only thing I can think of that currently offers something along these lines is StackExchange and related platforms. But while these websites are quite good at providing support, they don’t provide any form of guidance and have many flaws that could be fixed by a proper reference service. In particular, sites like StackExchange are completely impersonal and you only get answers from people who don’t know your background. Explaining for each question what you’re currently doing and what you already know is extremely laborious. Moreover, the quality of the answers certainly would be higher if people were paid for them. And last but not least, most of the sites suffer from an overly strict moderation policy that contradicts the principle of “staying out of people’s way”.

A “Reference Services to Educators-at-Large” would allow learners to get support, guidance and encouragement from someone more experienced who knows their background and is paid for his or her service. Moreover, if the system is based on reputation, not credentials, there’s certainly no shortage of people who can help.

Making the deschooled society a reality

Let’s imagine that all the puzzle pieces discussed in the previous section are in place. This would provide a complete framework for serious learners that has nothing to do with schools. Would schools then become completely irrelevant? Certainly not.

At this stage, arguably, the biggest remaining obstacle would still be the “discrimination-based-on-credentials” issue. Most people would continue to go to school because this is the only way to get the credentials that you need to avoid being discriminated.

I don’t think it’s realistic that there will be laws against “discrimination-based-on-credentials” anytime soon. Nevertheless, there is a realistic chance that the “learning web” becomes a success.

Some brave people would recognize its potential. These early adopters would become role models and more and more people would be attracted to the freedom offered by the alternative path. Simultaneously, companies will recognize that learning-web-learners are better hires such that credentials eventually become irrelevant. In particular, more and more companies will understand that “a test of a current skill level is much more useful than the information that twenty years ago a person satisfied his teacher in a curriculum in which typing, stenography, and accounting were taught.”

Moreover, the best teachers will welcome the opportunities offered by the learning web. In the current system, “schoolteachers are overwhelmingly badly paid and frustrated by the tight control of the school system.” Therefore, “the most enterprising and gifted among them would probably find more congenial work, more independence, and even higher incomes by specializing as skill models, network administrators, or guidance specialists.”

But even if all this happens, it would be foolish to believe that schools become completely irrelevant. Humans are primed to think in terms of binary opposites: schools = bad, learning web = good. In the real world, there is rarely such a clear line. Moreover, progress usually occurs in a manner of transcending and including not by wiping out what came before. So it’s likely that schools will continue to play an important role. However, they will be embedded into a larger ecosystem. This will allow them to focus on what they’re best at (e.g. homogenization) while the fulfillment of other educational goals is delegated to different kinds of structures.

In summary, irrespective of what you make of his other ideas, I’m convinced that Ivan Illich’s proposal for a learning web is a fantastic idea. I’m not entirely sure why not all the puzzle pieces have been built so far. But I would love to help to make it happen.